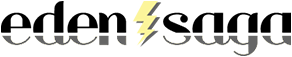

There are places forgotten by the tumult of the world, lands that modern maps brush over without naming them, as if their mere mention disturbed an ancient pact. The valley of the Cisse is one of those, peaceful and hidden in its secrets.

Val de Cisse

The Cisse is a small river lost between the overly well-ordered vineyards of the Loire country and the woods of oak trees which were once the moving frontier of the kingdoms of shadow. Its course captured that of the peaceful Loire. People used to fish there. The fishing carnets were sold by the communes where the fishery guards went out of style.

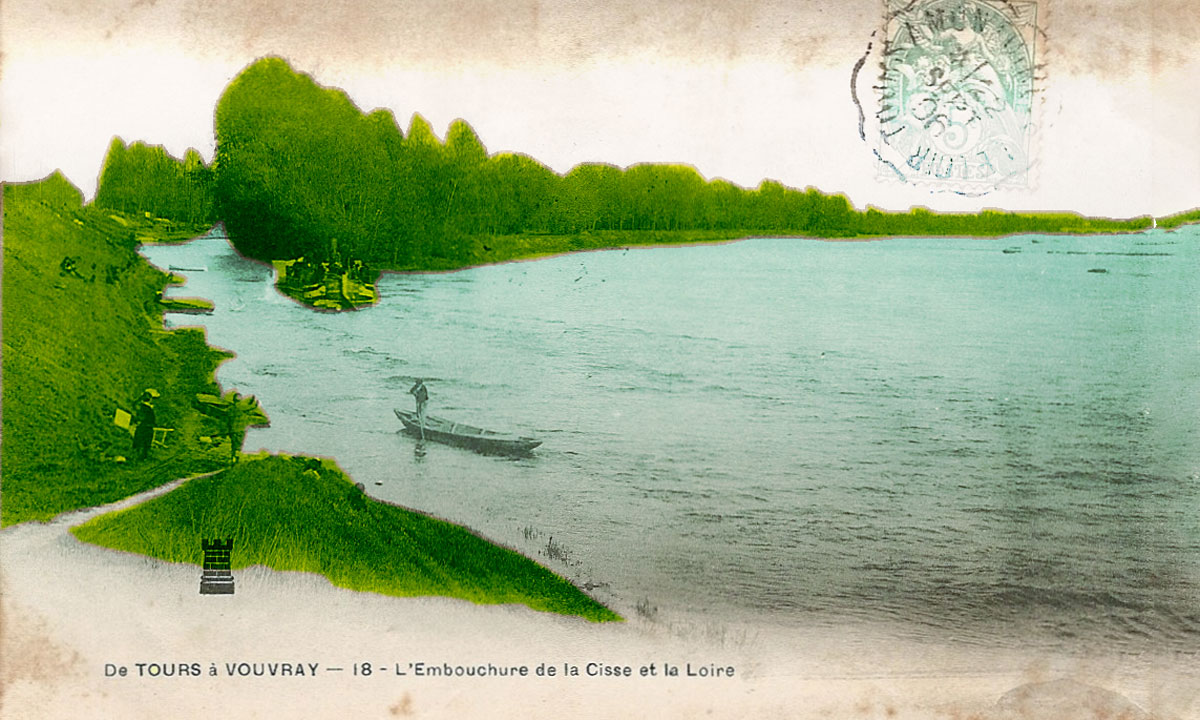

It is said that they still fish there, but more out of habit than out of desire, because fish are becoming scarce and the old people know that it is not for pike that we linger on these banks. The true fishermen, the silent ones, those who never look at the water without seeing in it the reflection of something else, hardly come to it anymore. Everyone, however, remembers the notebooks — of those little brown leather booklets that the communes or the fishery guards issued, a right stamped with silence and patience.

But all that is past, notebooks and guardians. Except one of each.

A Survivor

In a house half buried under the wild grass, on the north bank of the Cisse, remains a survivor that the village only mentions in a low voice: the last guardian of the Val de Cisse. It has no name, but several nicknames: the Taiseux, the Lock-keeper, the Watcher, sometimes the Passeur, as if each of these titles corresponded to a function older than the other. His notebook, he, is unique. A notebook whose last card opens, they say, towards the infra-world.

Indeed, the last map, the one that no one dares to turn, leads neither to the Landes mill nor to the island of Asnières, but to a deeper shore, older, which was once called the infra-world. A fracture in the course of waters, where the Loire itself, at a time too old for our archives, would have given its bed to the Cisse, as one gives a throne to younger and crazier than oneself. Since then, the river is no longer quite of this world.

Those who have glimpsed the last map speak of a reversed course, of a river that flows backwards through time, to a source which no one must approach without first having left something of oneself—his name, his shadow, or the memory of his childhood.

Taciturn

The taiseux says nothing, not a word. Or very rarely, between long silences. He waits. He wears his eternal canvas jacket which was green, with deep pockets and stitched elbows of old leather, and this black wool cap, pulled low on the nape. He would never have left the valley. This is not quite true. One saw him, a long time ago, on the docks of Tours, a morning of great fog, conversing with an old military man, retired cartographer.

The fisherman of the Val de Cisse is not a man like any other. He knows the lost names of the dead arms, those that no longer appear on the surveys since the cartographic monks have disappeared. He knows where water remembers, and where it forgets. He knows the exact times when the river reverses his breathing—that almost imperceptible thrill, when the air settles differently on the skin, when the light becomes stagnant and even insects suspend their ballet.

His knowledge, he does not share it. Guardian, he guards. Not only silures, it keeps treasures of memory, ancient confluences, thresholds, passes.

He can read stones. Not only their arrangement in the riverbed, but their color, their sleep density. He recognizes those who come from the bottom of the waters, from another layer, from another world that sometimes outcrops, memory drowned.

The Ultimate Notebook

And this notebook. Tanned leather, burnt edges, hand stitching, when we were still sewing things to last for centuries. A rather thin notebook, barely twenty pages, each covered with brown ink in fine, hieratic writing. A fishing notebook? Not really. Rather a collection of passages. A book of fords. Invisible tides. A valuable codex.

The guardian waits for the interstices—the exact time between the last ray and the first star, when the sky becomes milky and the river ceases to belong to men. There, he sits on his stone, opens the notebook, and whispers a litany in Latin of cooking, a false prayer that crows no longer understand.

The last Guardian has no age. It seems like he has always been there, in one of those incidental times that do not appear either on the dials or in the almanacs. The locals say he’s been there forever. When by chance the Taiseux drops a few words, his gaze always goes beyond the one who listens to him. He hears something else, a secret dialogue between roots and mud, this muffled complaint that the river pushes when it scrapes a memory.

He knows that under the Cisse flows another Cisse. A more serious, older, calmer layer, accessible to those who renounce any straight line. The infra-world does not allow itself to be reached, its truth is buried in the dream of a dead person.

Pierrot

Once, Pierrot, the baker’s son dared to sit next to him. It was the equinox. The Taiseux handed him a black and smooth pebble. He said: “This one comes from downstairs.

– From where below?

– From below the underside.

Then he stopped. That’s all. Pierrot never forgot. He grew up, left the valley, lived his life, but he kept this pebble in a drawer, and sometimes, at the heart of too quiet nights, he feels it vibrate against his palm.

He had gone far away, like all those who are afraid of staying too long. Pierrot felt that if he stayed, something would eventually claim his pebble. He had first kept it in a child’s treasure box, among a few marbles, a milk tooth, a debarked postcard. Then, as an adult, he attempted to part with it. He slipped it into a drawer, then into a shoebox, then into a suitcase at the bottom of a cellar. But the pebble was coming back.

Not literally—no, he wasn’t crazy. But every time he dreamed, he dreamed of water. A water that didn’t flow, that breathed. Of a river without reflection. And always, in these dreams, he felt the presence of the fisherman. Not as a memory, but as a call—a gaze on him from the bank, motionless, patient.

Brown Ink

On the day he turned forty, he received a letter. No sender. A brown ink, four words: “The notebook awaits you.” He left his work, turned off his phone, bought a train ticket. The journey was long, especially towards the end. The closer he got to the valley, the more the world lost its angles, speeds, and sharp contours. At the station, no taxi. He walked.

When he arrived at the edge of the Cisse, nothing had changed. Or rather: everything had changed, imperceptibly. As if the valley had continued to breathe in his absence, but more slowly. The same stone bench. The same poplars, at higher heights. And, under the arch of an old willow tree, the silhouette of the fisherman.

The guard was there. Exactly as in his memory. Neither older nor more curved.

After an interminable silence, the fisherman took out the notebook. He opened it at the last page—the one that no one had ever seen. – — You can look.

But he added nothing. Neither warning nor advice. For he knew that this kind of journey only begins within, and that every word would be an obstacle. The man looked at the page. And something, immediately, gave in to him. An ancient, invisible dam, a secret lock that he had carried since childhood. He did not read a map. He saw a direction.

Pierrot doesn’t know how long he stayed there, his eyes resting on the last page. A minute. A whole life. The world had stopped. His heart too. And he saw.

Just a Flowing Shape

There was no precise route, no trail or itinerary. Just a flowing, moving shape, as if the living ink was continuing its path on the surface of the paper. He recognized there a loop, a meander that he knew without ever having seen. It was a map, yes, the map of an interior territory. A black pebble also appeared — placed at the junction of two current lines. And further on, almost erased, a name… a sigh.

What he then felt was not a human emotion. It was a slip. As if an invisible hand stripped him of everything he believed himself to be. The man he had become, with his scars, his habits, his polite forgetfulness, was gradually unraveling, and something more ancient emerged. Something more naked. He felt crossed.

Around him, the outlines of the valley gently wavered. The willow shimmered from a foliage that was no longer that of the current season. The stone bench seemed both mossy and new, as if it had just been carved from granite. He heard, in the distance, bells. But it wasn’t the bells of a bell tower. It was something else. A call maybe. Or a sound memory. And in that resonance, there were voices.

Voices

These voices, he knew them without ever having heard them. A woman’s range, serious, with an inflection that reminded him of his grandmother’s. A man’s stamp, deep, calm, unknown, but that he recognized. They were not ghosts. They were neither there nor elsewhere. They were just… reaching it. Like an underground light, filtering little by little through the layers of forgetfulness.

Then he understood: time had no weight here. It wasn’t a line. It was a tablecloth. A slow-moving water, where generations settled on each other, like dead leaves on a pond. And he, at that moment, had pierced the surface.

An Ink Mirror

He did not turn to the fisherman. He knew that he no longer needed him. The man had not disappeared — he had entered into the silence of accomplished things. The notebook, on the other hand, was always open on his lap. But the page had changed. At present, there was no longer a card. Just an ink mirror in which he looked at himself without seeing himself. And behind this reflection, very gently, the infra-world opened the door.

He did not move. It would have been a sacrilege. For he felt that even a gesture, the most minute one, risked breaking the balance of this moment—as one brushes against the surface of a still water and as soon as the circles go to disturb the inverted sky it reflects.

Everything Was True

Around him, the landscape was no longer quite the same. Or rather: it had become all landscapes at once. The path of his youth was superimposed on that of his great-grandfather’s childhood. The shadow of the old collapsed bridge half reappeared, as in a palimpsest—a stone, an arch, a trace, nothing more, but it was enough. He saw there, a stone’s throw from him, a figure whom his mind recognized as his uncle, dead without issue in 1939, and who nevertheless smiled at him with the connivance of a brother.

None of this made any sense. But everything was true.

He finally understood that the valley was a node. Not a fixed place, but an interweaving of time. A point of condensation where the living, the dead, the unborn, and the forgotten circulated like groundwater on the same ground. Some of these currents had not been rising to the surface for centuries. Others sometimes arose, in a glance, a smell, a dream. And he, at that moment, was the confluent.

Identity Shift

He suddenly remembered gestures that he had never done. A calloused hand towards a hitch. A slow walk by the edge of a river before the dikes. A voice shouting a forgotten name in the winter wind. He carried within him, at that moment, memories that did not belong to him, but were entrusted to him. Not to possess them—but to carry them for a moment, as one carries a flame between two shelters.

And there was this new, overwhelming sensation: that of being watched from the inside. As if an ancient eye, planted in the center of itself, opened little by little and contemplated, without judgment, but with immense tenderness, the thousand faces it had borne through time.

He no longer knew if he was a man or a memory. He no longer knew if he was there to discover or to remember. But he did not tremble. He wasn’t afraid. Because in this shift of identity, in this vertigo of simultaneity, there was a sovereign peace—the peace of those who know that they have never been alone. That others have watched before them. That others are still watching.

And that, now, it was his turn to watch.

Alain Aillet Sayings

- Song of Roots

- Aurora Into Resonance

- Aide-memoire

- The Chickadee

- Harvey the Elder

- She and the Painted Cave

- The Garden of Facts

- The Hardware Fault 2

- Shadows Hardware 1

- Message in a Bitter

- The Distorted I

- Star Traveler

- The Purple Ribbon

- Immortals Café

- Aurochs Ford 2

- Aurochs Ford 1

- Pech Merle

- The Sons of Light

- Eternally

- Planet E

- From Tautavel To Bozouls

- Odious Odin, Frightening Freya

- Teutonic, Archetypal Language

- Planet Babel

- Sounds And Languages

- The Golden Tongue