In Turkey, a very ancient unknown civilization surprises the archaeologists with its religious art. Temples, places of ritual in every house, and wonders of craft … Had this civilization fallen from heaven?

The civilization of Çatal Hüyük offers another insoluble riddle, the total absence of past evolutionary traces. Here is the story of its discovery. Çatal Hüyük, the Fork Hill, stands in the plain of Konya, in central Anatolia, on the banks of the river Çarsamba. In 1961, the archaeologist James Mellaart went there to conduct excavations. Only a mound was visible then, with remains of pottery and very ancient fires. Soon the excavations reveal an ancient city.

The hill covered a network of tombs and houses of a proto-Neolithic community from the 7th millennium BC. Shock and awe. In the Sixties, we knew almost nothing of the Neolithic period in this country. (source)Çatal Hüyük and the Neolithic Revolution by Jean-Louis Huot, Archaeological Records, December 2000 And suddenly, James Melaart discovered the largest Neolithic site of the Middle East – if we exclude the troglodyte cities of Cappadocia wrongly estimated latest. Founded around -7000, it became an important center from -6500 to -5700. The city and its suburbs, at their peak, covered 13 hectares.

The city was home to 5,000 people; it had a developed organization and culture, maintaining a long-distance trade and producing quality crafts. It contained shrines with wall paintings, figurines and burials, evidence of a complex religious life. Some statuettes remind of the prehistoric Venus of Germany. And the graffitis evoke those of the Altamira Cave, yet much more ancient. Is it a sign that they are derived from the same cultural matrix?

In the surrounding countryside, they grew wheat, barley, peas, chickpeas, lentils, vetch; they picked apples, pistachios, bays, almonds and acorns. The meat was provided by fishing and hunting (deer, wild boar, wild ass). While the region allows a dry farming, we note a manipulation of water probably necessary for cultivating flax or obtaining a higher yield for cereals. But frankly, no one knows indeed.

In any case, Neolithic people were fond of pipes and drains of all kinds, not just in the Andes. The site was a center of trade for many commodities (wood, obsidian from the volcano Hasan Dag, flint, copper, shells from the shores of the Mediterranean), and its craftsmen mastered the copper smelting (most ancient attestation of metallurgy in the Middle East) and had specialized in many craft productions.

Melaart brought to light a wide variety of quality items: arrowheads, spearheads, obsidian and flint daggers, stone maces, stone and baked clay figurines, textiles, wooden and ceramic crockery, jewels (beads and copper pendants). We note that these remote ages were much more civilized than more recent periods. Where did these know-how, vanished afterwards, come from? Where did these people get this art of trade and crafts from? Always the same unanswered questions.

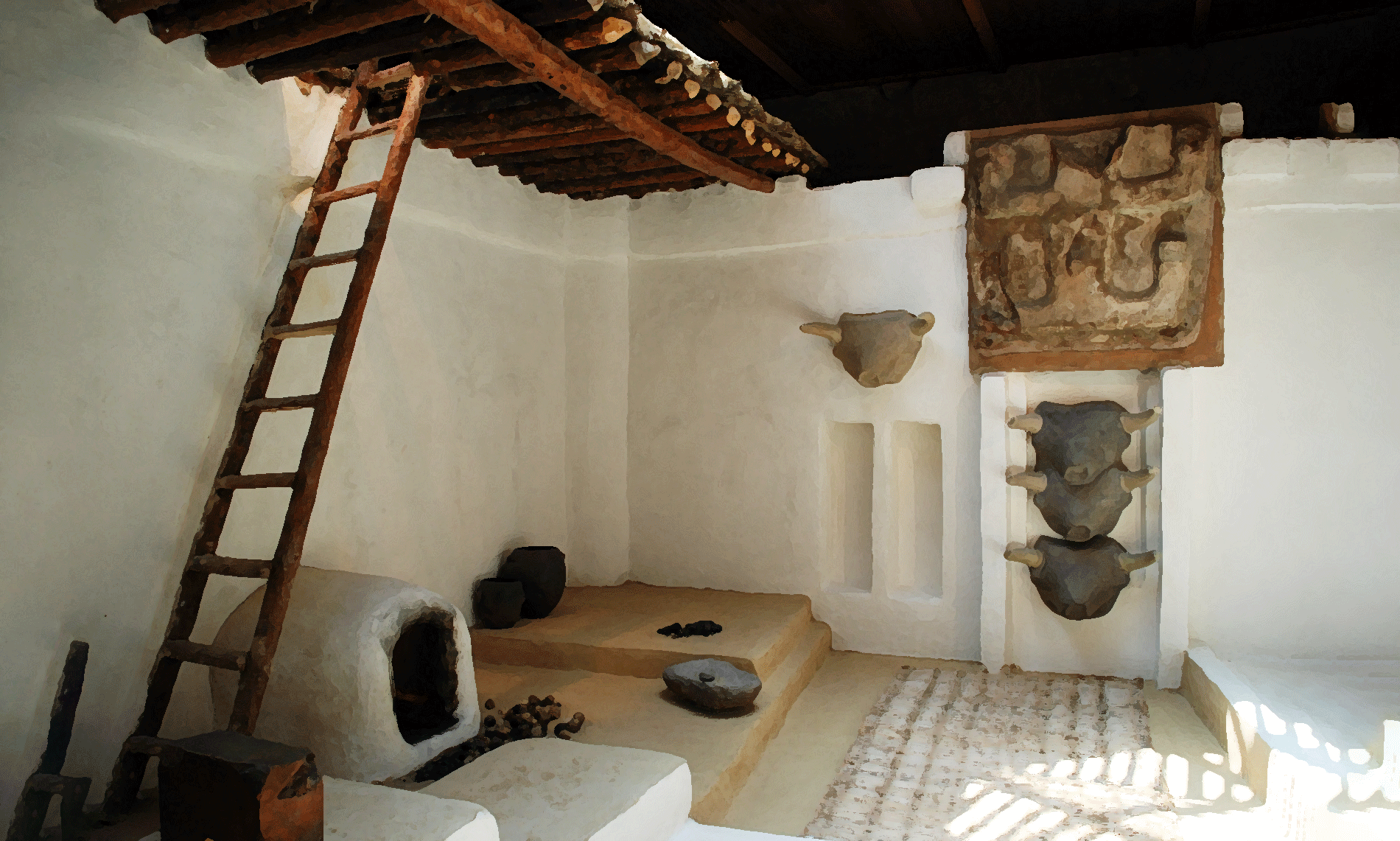

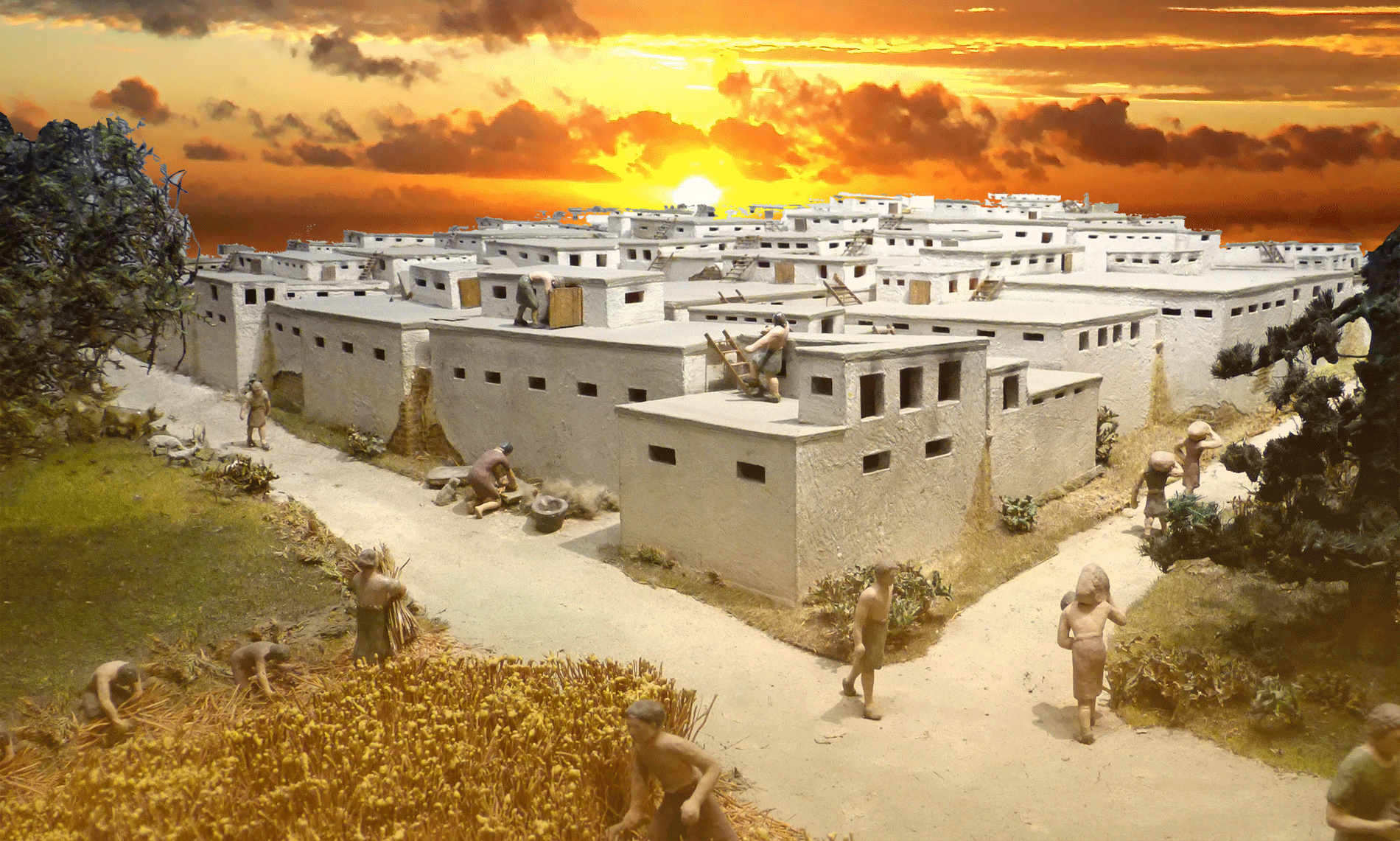

The houses were closed up against each other, without any street or passage, only accessible by wooden ladders placed here and there. They were built in mud bricks covered with plaster and usually included a common room of 20-25 square meters and annexed rooms. The main room had benches and platforms for sitting and sleeping, a raised rectangular foyer and a vaulted bread oven.

But the most beautiful, Melaart did not find it in ordinary houses. Many shrines contrasted by their refined decoration: frescoes or wall paintings, modeled reliefs, animal skulls and figurines. In some places, the shrines were so numerous that Melaart thought to be in a specialized area. Further excavations showed thereafter that the shrines were everywhere in large numbers. It is even the main feature of this archaic culture.

The bodies of the dead were deposited under the resting platforms in shrines and homes, and piled up over the years and generations, suggesting an elaborate cult of ancestors. Before being buried, along with precious objects, the bodies of the dead were entrusted to vultures and carrion insects. (source)Wikipedia The interest of the site also lies in its unique iconography.

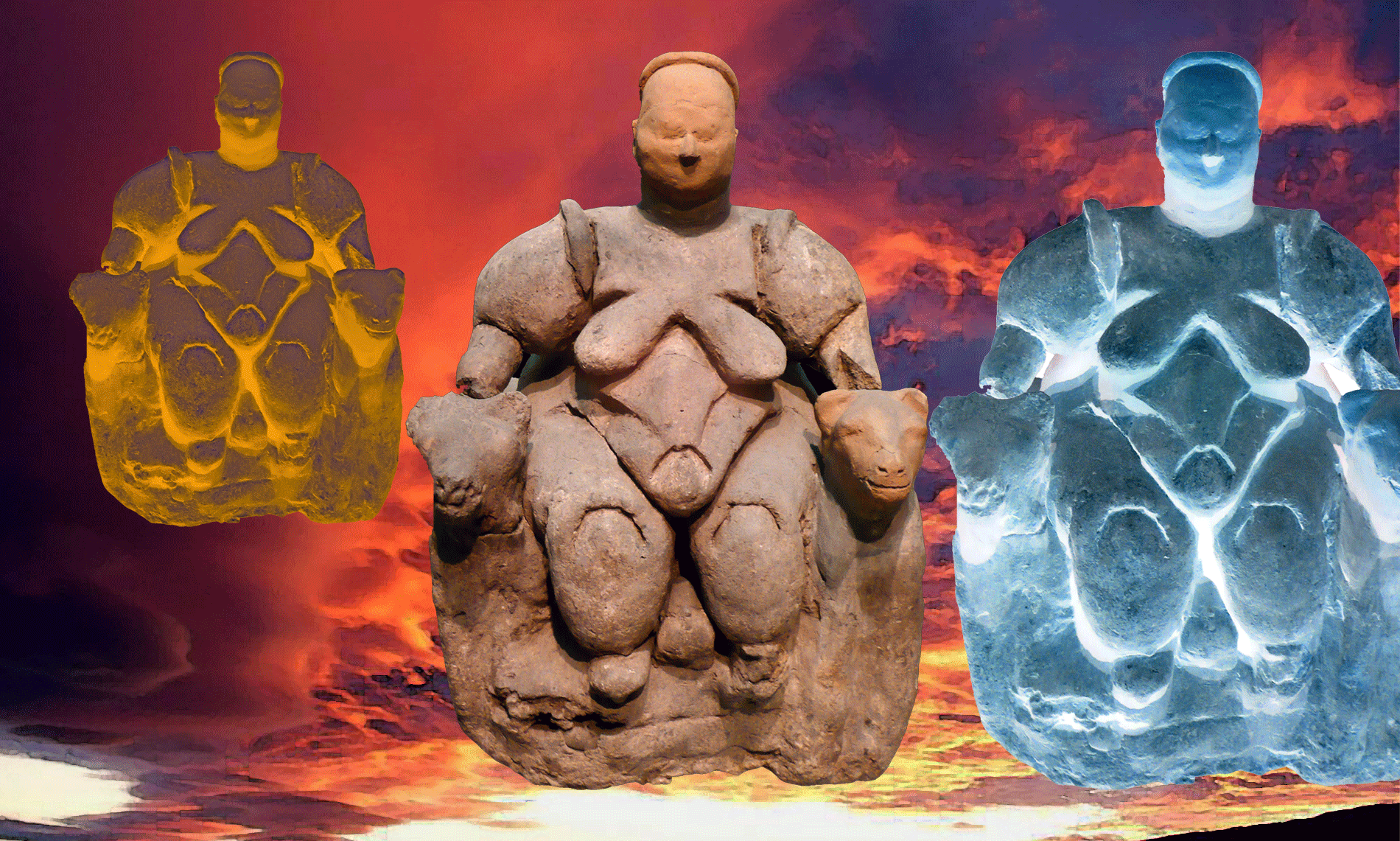

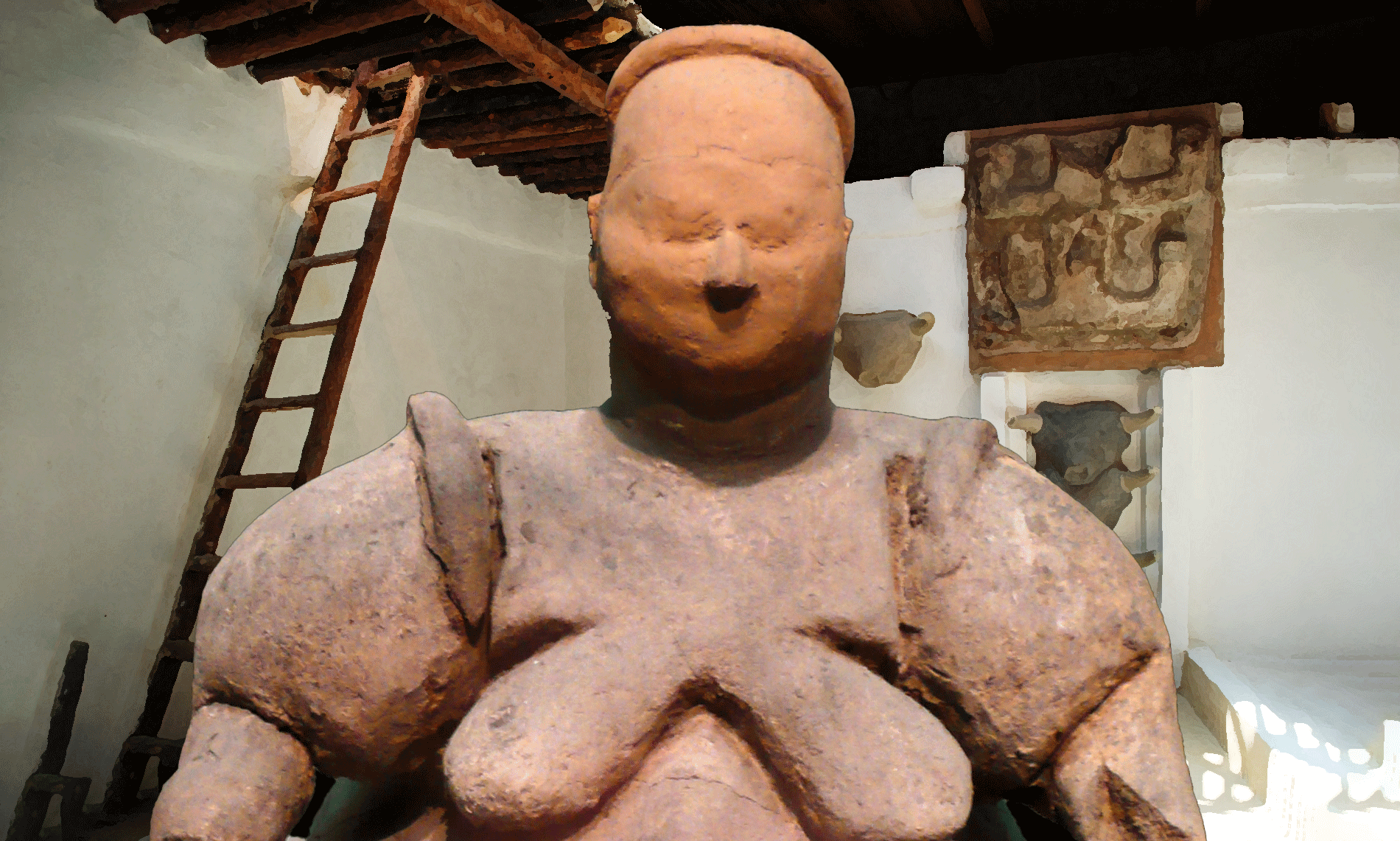

Everywhere, female figurines evoking a cult of fertility, like this woman giving birth seated on a sort of throne adorned with cats. The wall paintings also suggest a cult of mother goddess, often pregnant or parturient, surrounded by leopards and bulls symbolizing the gods. The reliefs could also represent a woman’s breasts. Melaart also discovered strange masculine figures, like this naked man riding a bull.

The mother goddess is the guarantor of rebirth, immortality and fertility. Symbol of eternal femininity, she appears in the midst of many triangles, the body schematized until abstraction, often accompanied by her symbolic animal the bull which horns are reflected in her body. It is the symbol of her offspring to which she will give life and death by the ritual sacrifice of the bull dedicated to her, to ensure the fertility of the earth and the rebirth of nature after the winter frosts.

This universal rite related to the agriculture cycle is still prevalent today in the remote countryside of Anatolia. (source)Ody Saban 1986 The walls of some houses are decorated with frescoes depicting hunting, bulls, stags, rams, vultures and headless men, sometimes geometric patterns; on the walls are modeled in relief female characters or animals and on the walls delimiting the benches, clay bucranes with real horns. (source)Peoples of Ancient East, volume 1, by Jean-Louis Huot

Considering the extraordinary level of detail and decoration of the buried constructions, jewels, tools, weapons and wall paintings, it was soon clear to Melaart that this culture was very advanced in its beliefs, its lifestyles and its arts.

And this city is one of the most ancient ever discovered cities, which is not the least paradox. The more we go back in time, the more peaceful and advanced the behaviors seem, the more finely wrought craft is. Nothing similar had ever been found, in Turkey or elsewhere.

Melaart got surprised: “How could they, for example, polish a mirror of obsidian, which is a hard volcanic glass, without scratching it? Or drill through stone beads (including obsidian) holes so thin that they are impervious to modern steel needles? When and where did they learn to extract through smelting copper and lead, metals certified in Çatal Hüyük from -6400?” (source)Catal Hüyük : A neolithic town in Anatolia, by James Mellaart Such a technical nature does not appear at one go. For Melaart, Çatal Hüyük represents the culmination of an “extremely ancient strain”.

Why not that of the Serpent People? Or that of the Pyramids? These civilizations date back to Paleolithic times, far before the end of the last ice age, the Wurm, between -120000 and -8000, when an ice sheet covered much of Europe.

On this same site, the oldest known representation of a drum was discovered in a fresco. More than thirty characters, some of which playing percussions, dance around a huge bull. Two characters hold percussion instruments that remind strangely of the berimbau, a Brazilian instrument originally from Africa. Moreover, let us note the color of the dancers’ skin. Some are black, others white, or half-white.

Blacks are sometimes covered with a leopard skin. All is as if the inhabitants of this Neolithic city belonged to the two ethnic groups, like the first Egyptians, and like the Atlanteans before the flood. One more proof that the Nubians, powerful black African civilization, had spread to Asia as well as in the Americas, long before the start of the history of Europeans. The protohistory is full of migrations, conquests, oceanic crossings as if the planet of that time was very small. Or as if people had rapid means of communication…

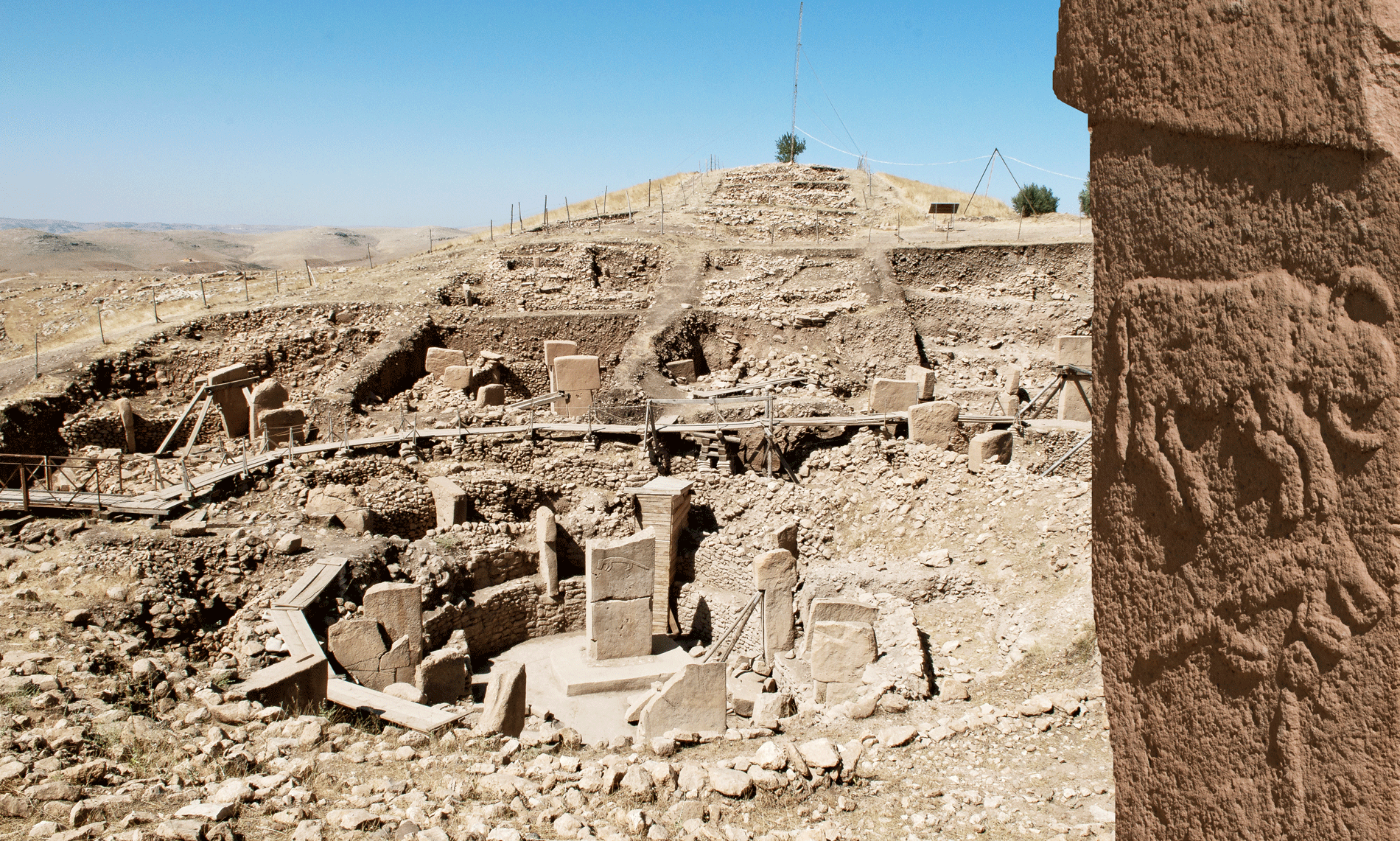

Still in Southern Turkey, near they Syrian border, we discovered the oldest stone temple in the world. Gobekli Tepe would be some 11,500 years old, probably built by the last hunter-gatherers, just before agriculture. The builders of this temple could be the first growers of oat: DNA analysises of domestic oats compared to wild oats showed that the strain used was from Mount Karacadag, next to the site.